Alise Tifentale, "Working the Labor-Leisure Machine: Proposal for a Photography Museum Without Images," Riga Technoculture Research Unit (RTRU), Season 1 (February 1, 2023), https://www.rtru.org/under-the-hood/participants/alise-tifentale

Read my article on the RTRU platform here: https://www.rtru.org/under-the-hood/participants/alise-tifentale

RTRU - www.rtru.org - is curated by Elizaveta Shneyderman and Zane Onckule, designed and coded by Becca Abbe.

Abstract:

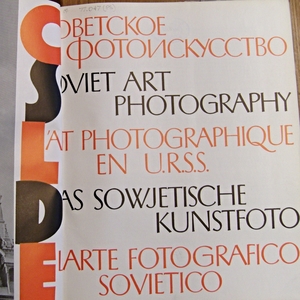

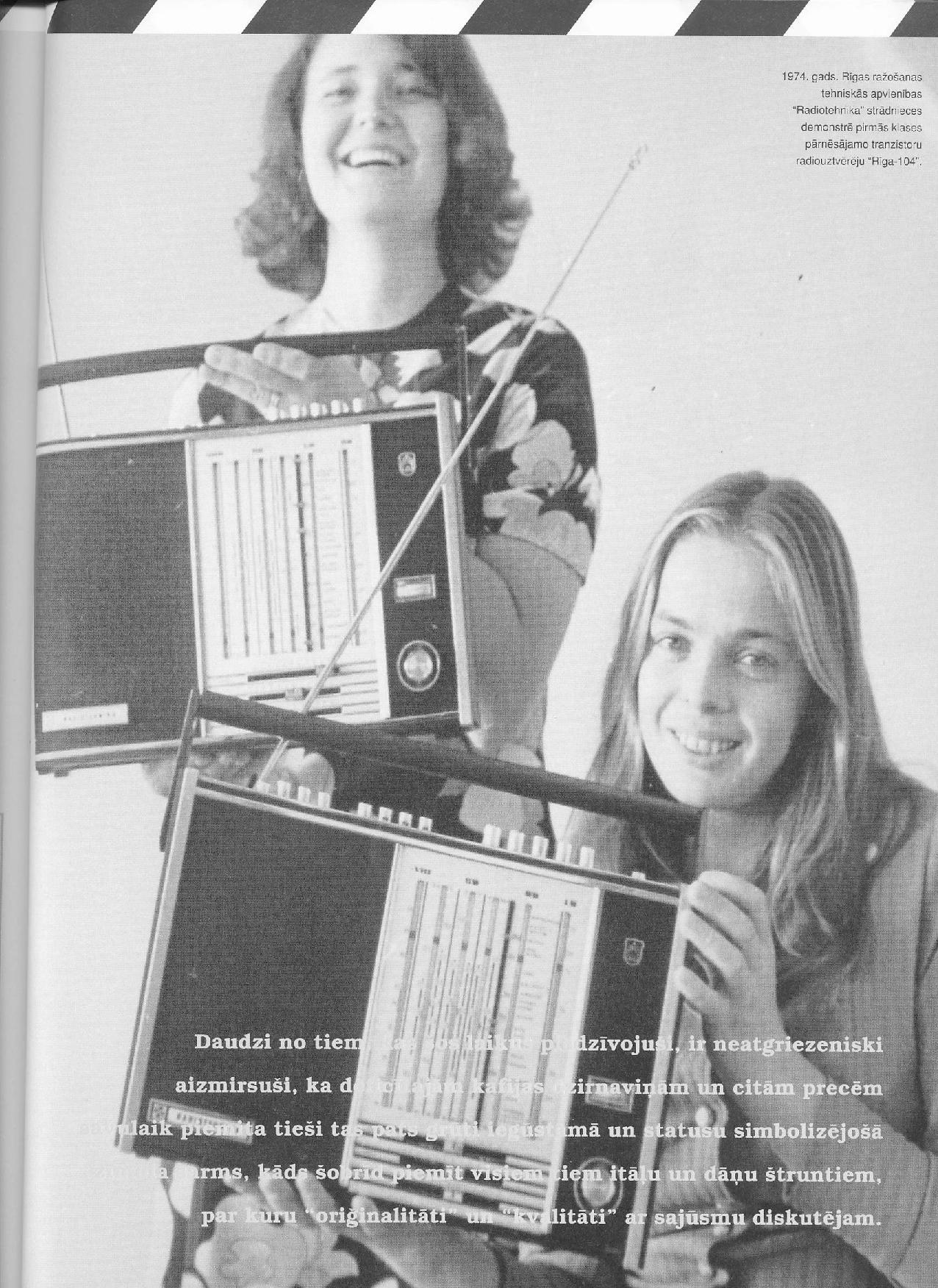

Almost seventy years ago, André Malraux introduced the concept of a museum without walls (the “musée imaginaire”) containing photographic reproductions of artworks; he furthermore developed a detailed analysis of the shortcomings and benefits of such a “museum.” I am using Malraux as a starting point for thinking about photography through the lens of a museum without images. Central to my museum is the understanding of photography as a practice, an apparatus, and a form of social interaction. The museum examines photography as a complex mechanism where labor and leisure overlap; photography can simultaneously be a means of production, a source of entertainment, and a commodity for consumption. My method suggests a subversion of the patriarchal and Euro-centric concept of a museum as a collection of valuable masterpieces. Instead, this museum exhibits ideas as works in progress. No doubt, there are also images in this museum, but they play the role of footnotes. Even more importantly, at the time of their making, these images exist(ed) outside, or on the margins of, the mainstream art world.

Central to this proposed museum is the understanding of photography as a practice, an apparatus, and a form of social interaction. The museum examines photography as a complex mechanism where labor and leisure overlap. Photography can simultaneously serve as a means of production, a source of entertainment, and a commodity for consumption. This essay introduces five rooms of the museum. These rooms offer ways of viewing photography as part of contemporary technological culture, with a focus on concepts like the labor-leisure machine, the networked camera, photography without images, obsolescence/prescience, and human-machine relationships.

From the publishers about the concept of RTRU - www.rtru.org:

“Part research journal, part art and writing publisher, part hub for developments in emerging media, RTRU brings an interdisciplinary and technicity-centered approach to the status quo of contemporary art programming. Season one, Under The Hood, looks at the technical processes and economic and social structures of production that profoundly shape visual culture. Our first season considers the museum without images; the effusive “student body”; labor history; “the factory of phenomena,” the paradigmatic worksite of contemporary media culture; and much more.

In order to understand how imaging strategies produce the aesthetic effects that we frequently and unconsciously observe in the world, we must first understand the infrastructure for how these images are made, or go “under the hood.” The way visual culture comes to be constructed is at the center of these investigations: the real-time simulations and the skeletal rigs that form the underwire of thrashing corpses, the labor laws which structure capitalist workflows, the technologically dependent student body, the visible signature of video art tropes and their affective contours, many of which have become increasingly prevalent. All of these examples belie their beginning as metrics, inputs, algorithms, and other coding languages assigned by animators, programmers, and policymakers. The images produced by these original technical apparatuses thus introduce a new level of estrangement wherein the major referent is no longer the physical world, but the technical culture behind the curtain.”