This, however, could happen only because a demand or desire for such technological innovations had already been articulated in society. Thus also the appearance of the selfie as a new sub-genre of popular photography is historically time-specific: it could emerge only in a moment when several technologies have reached a certain level of development and accessibility and when a “burning” human desire had emerged, referring to Geoffrey Batchen’s highly influential book (Burning with Desire: The Conception of Photography (Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press, 1997)). Although many photographers—well-known artists and enthusiastic hobbyists alike—have made self-portraits since the very early days of photography, scholars have confirmed that “self-portraits did not become a mundane practice until the digital camera converged with the mobile phone" (Marika Lüders, Lin Prøitz, and Terje Rasmussen, "Emerging Personal Media Genres," New Media & Society 12, No. 6 (2010): 959).

Furthermore, the convergence of the camera with smartphone is not all that is needed for a selfie—there has to be a human desire to make such picture and—equally important—to share it with one’s peers. According to the definition by the Oxford Dictionaries, a selfie is “…a photograph that one has taken of oneself, typically one taken with a smartphone or webcam and shared via social media.” This definition neatly sums up all three key activities that are essential for the selfie: taking a photographic image of oneself, using a camera on one’s smartphone, and sharing this image on social media networks. While other scholars have introduced the term “networked image,” I would like to suggest a slightly different term that shifts the focus more toward the apparatus that produces the image: the networked camera.

The networked camera is a curious hybrid: an image-making, image-sharing, and image-viewing device whose necessary features include hardware such as easy to use smartphone with a built-in camera, the availability of wireless Internet connection, the existence of online image-sharing platforms, and the corresponding software, the ‘invisible hand’ that drives the devices and service platforms. This combination facilitates a streamlined production, dissemination, and consumption of visual information.

The concept of the networked camera helps to understand the selfie as a hybrid phenomenon that merges the aesthetics of photographic self-portraiture with the social functions of online interpersonal communication. Already before Instagram and the selfie, some scholars had noted the dualism of online image-sharing practices—the coexistence of their aesthetic and social functions—and had observed that the emphasis in analysis most often tends to be put on the “social life of the networked image”, while overlooking the image itself (see, for example, Daniel Rubinstein and Katrina Sluis, “A Life More Photographic, Mapping the Networked Image,” Photographies 1, No. 1 (2008), 9-28). Social sciences and media studies indeed provide a solid theoretical and methodological basis for thinking about identity construction and performance in social network sites (see, for example, Zizi Papacharissi, ed., A Networked Self: Identity, Community and Culture on Social Network Sites (New York: Routledge, 2011)). Our task remains to re-connect the medium with the message and aesthetics with functionality.

Just like the networked camera is more than only a new type of camera, the selfie is more than an image. Although the selfie is reminiscent of traditional photographic self-portraiture, its other essential attributes include metadata, consisting of several layers: automatically generated data (like geo-tags and time stamps), data added by the user (hashtags), and data added by other users (comments). Another, no less important attribute of the selfie is the instantaneous dissemination of the image via Instagram or similar social networks that makes the selfie significantly different from its earlier photographic precursors (see Kandice Rawlings, “Selfies and the History of Self-Portrait Photography,” November 21, 2013). As Sonja Vivienne and Jean Burgess have observed, “much more important than digital photography’s influence on the practice of taking photographs, then, are the ways in which the web has changed how and what it means to share photographs" (Vivienne and Burgess, “The Remediation of the Personal Photograph and the Politics of Self-Representation in Digital Storytelling,” Journal of Material Culture 18, No. 3 (2013), 281. Emphasis in original).

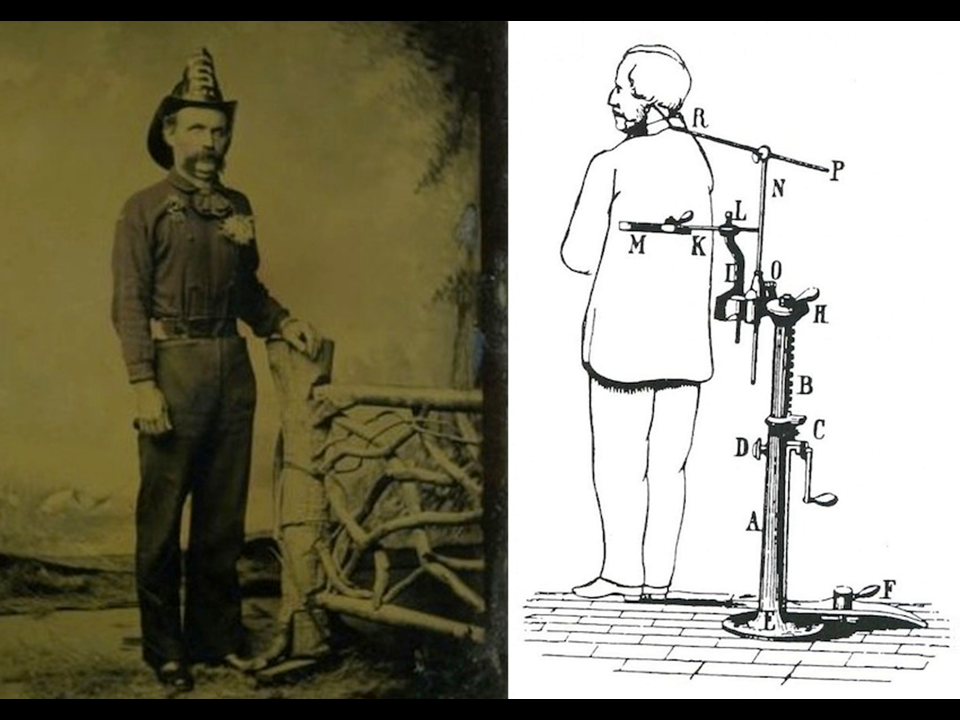

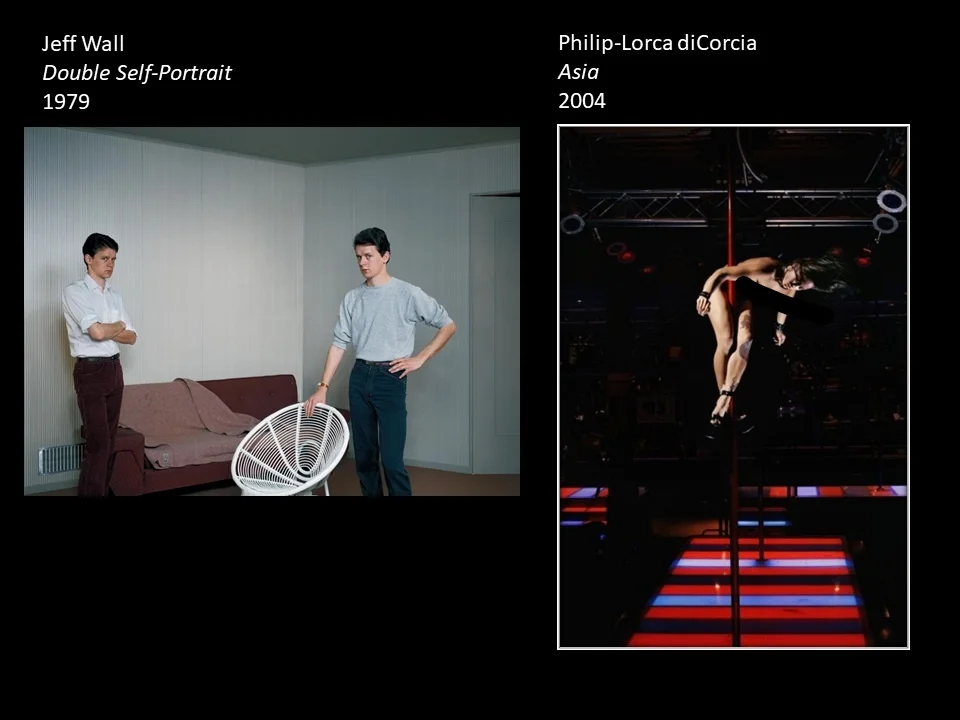

These considerations can partly serve as an answer to those who tend to apply the term “selfie” retroactively to photographic self-portraits made before c. 2010. While there are lots of self-portraits in the history of photography that look seemingly similar to selfies—self-portraits in mirrors, self-portraits made while holding the camera in one’s extended arm etc.—these images are not selfies because they are not products of the networked camera, they were not made with a camera of one’s smartphone and were not shared on social media networks. As simple as that.