“Following the Invisible Hand: The Role of Photo Clubs, Magazines, Exhibitions, and Curators in Latvian Photography, 1960–2000” is a commissioned research article for a volume of articles Ten Episodes in Art of the Second Half of the 20th Century in Latvia. Edited by Elita Ansone. Riga: Latvian National Museum of Art, 2019. In English and Latvian.

Read moreBrazilian Participation in FIAP, 1950–1965

“Brazilian Participation in the International Federation of Photographic Art (FIAP), 1950–1965” (provisional title) is a commissioned research article for a book about photography in Brazil, Fotografia Moderna (provisional title), edited by Helouise Costa and Heloísa Espada to be published by Instituto Moreira Salles, São Paulo, Brazil, in 2021.

Read moreFifty Year Eclipse: Illuminating the Forgotten Legacy of Photographer Vilis Rīdzenieks

"Fifty Year Eclipse: Illuminating the Forgotten Legacy of Photographer Vilis Rīdzenieks" inVilis Rīdzenieks. Edited by Katrīna Teivāne-Korpa. Riga: Neputns, 2018.

Read morePhotography in Latvia, 1970–2000

“Photography in Latvia, 1970–2000,” in The History of European Photography 1970–2000 (vol. 3) (Bratislava: Central European House of Photography, 2017). ISBN 9788085739701.

Read moreThe Selfie: More and Less than a Self-Portrait

“The Selfie: More and Less than a Self-Portrait,” in Moritz Neumüller, ed., Routledge Companion to Photography and Visual Culture (London, New York: Routledge, 2018), 44–58.

Read moreCompetitive Photography and the Presentation of the Self

Alise Tifentale and Lev Manovich, "Competitive Photography and the Presentation of the Self" in Jens Ruchatz, Sabine Wirth, and Julia Eckel, eds., Exploring the Selfie: Historical, Analytical, and Theoretical Approaches to Digital Self-Photography (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 167-187.

Read morePhotography: Taken, not Made

"Photography: Taken, not Made," in Arnis Balčus, ed., Territories, Borders, and Checkpoints (Riga Photomonth Catalogue) (Riga: Society Riga Photomonth, 2016), pp. 90-95. ISBN 978-9934-14-852-1.

The essay accompanied an exhibition of experimental photography, Paintings and Sculptures, curated by Arnis Balčus and Elīna Sproģe as part of Riga Photomonth programming. The artists in the exhibition: Eduards Gaiķis, Valters Jānis Ezeriņš, and Līga Spunde. The exhibition took place at the Exhibition hall of the Latvian National Library, Riga, May 7-30, 2016.

Read moreThe Networked Camera at Work: Why Every Self-Portrait Is Not a Selfie, but Every Selfie is a Photograph

"The Networked Camera at Work: Why Every Self-Portrait Is Not a Selfie, but Every Selfie is a Photograph," in Santa Mičule, ed., Riga Photography Biennial 2016 (Riga: Riga Photography Biennial, 2016), 74-83. ISBN 9789934148613.

This article focuses on the role of technologies in defining and understanding the selfie. While there is danger of slipping into oversimplified technological determinism, we have to admit that the role of technologies in visual culture, and especially photography, is often underestimated. Could phenomena like the selfie really be just a byproduct of the advancement and accessibility of digital image-making and image-sharing technologies? Or rather new and emerging photographic practices shape the design and features of hardware and apps, such as the introduction of the camera (and then the second one) in smartphones and appearance of Instagram and other image-sharing platforms? In this article, I examine the difference between the way datasets of selfies are being constructed for research and comparison, and how selfies are consumed and experienced in their natural habitat, the live flow of images on Instagram.

Recently an artist friend claimed in a conversation that he thinks that people, including himself, have made “selfies” all the time, even before the appearance of social media and smartphones. He said he used the word “selfie” just as a shorter version of “self-portrait.” Indeed, “selfie” is closely related to the concept of “self-portrait,” but it is more than that.

Looking back into the history of photography, the cheap and easy to use Kodak Brownie cameras around 1900 gave rise to popular and amateur photography, introduced the snapshot, and established a tradition of family photograph albums. Similarly, around 2010 we saw a rise of a new kind of image-making device, the smartphone with a built-in camera and wireless connection to the Internet. Availability of such devices on mass market was followed by a formation of new sub-genres of popular photography, such as the selfie.

This, however, could happen only because a demand or desire for such technological innovations had already been articulated in society. Thus also the appearance of the selfie as a new sub-genre of popular photography is historically time-specific: it could emerge only in a moment when several technologies have reached a certain level of development and accessibility and when a “burning” human desire had emerged, referring to Geoffrey Batchen’s highly influential book (Burning with Desire: The Conception of Photography (Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press, 1997)). Although many photographers—well-known artists and enthusiastic hobbyists alike—have made self-portraits since the very early days of photography, scholars have confirmed that “self-portraits did not become a mundane practice until the digital camera converged with the mobile phone" (Marika Lüders, Lin Prøitz, and Terje Rasmussen, "Emerging Personal Media Genres," New Media & Society 12, No. 6 (2010): 959).

Furthermore, the convergence of the camera with smartphone is not all that is needed for a selfie—there has to be a human desire to make such picture and—equally important—to share it with one’s peers. According to the definition by the Oxford Dictionaries, a selfie is “…a photograph that one has taken of oneself, typically one taken with a smartphone or webcam and shared via social media.” This definition neatly sums up all three key activities that are essential for the selfie: taking a photographic image of oneself, using a camera on one’s smartphone, and sharing this image on social media networks. While other scholars have introduced the term “networked image,” I would like to suggest a slightly different term that shifts the focus more toward the apparatus that produces the image: the networked camera.

The networked camera is a curious hybrid: an image-making, image-sharing, and image-viewing device whose necessary features include hardware such as easy to use smartphone with a built-in camera, the availability of wireless Internet connection, the existence of online image-sharing platforms, and the corresponding software, the ‘invisible hand’ that drives the devices and service platforms. This combination facilitates a streamlined production, dissemination, and consumption of visual information.

The concept of the networked camera helps to understand the selfie as a hybrid phenomenon that merges the aesthetics of photographic self-portraiture with the social functions of online interpersonal communication. Already before Instagram and the selfie, some scholars had noted the dualism of online image-sharing practices—the coexistence of their aesthetic and social functions—and had observed that the emphasis in analysis most often tends to be put on the “social life of the networked image”, while overlooking the image itself (see, for example, Daniel Rubinstein and Katrina Sluis, “A Life More Photographic, Mapping the Networked Image,” Photographies 1, No. 1 (2008), 9-28). Social sciences and media studies indeed provide a solid theoretical and methodological basis for thinking about identity construction and performance in social network sites (see, for example, Zizi Papacharissi, ed., A Networked Self: Identity, Community and Culture on Social Network Sites (New York: Routledge, 2011)). Our task remains to re-connect the medium with the message and aesthetics with functionality.

Just like the networked camera is more than only a new type of camera, the selfie is more than an image. Although the selfie is reminiscent of traditional photographic self-portraiture, its other essential attributes include metadata, consisting of several layers: automatically generated data (like geo-tags and time stamps), data added by the user (hashtags), and data added by other users (comments). Another, no less important attribute of the selfie is the instantaneous dissemination of the image via Instagram or similar social networks that makes the selfie significantly different from its earlier photographic precursors (see Kandice Rawlings, “Selfies and the History of Self-Portrait Photography,” November 21, 2013). As Sonja Vivienne and Jean Burgess have observed, “much more important than digital photography’s influence on the practice of taking photographs, then, are the ways in which the web has changed how and what it means to share photographs" (Vivienne and Burgess, “The Remediation of the Personal Photograph and the Politics of Self-Representation in Digital Storytelling,” Journal of Material Culture 18, No. 3 (2013), 281. Emphasis in original).

These considerations can partly serve as an answer to those who tend to apply the term “selfie” retroactively to photographic self-portraits made before c. 2010. While there are lots of self-portraits in the history of photography that look seemingly similar to selfies—self-portraits in mirrors, self-portraits made while holding the camera in one’s extended arm etc.—these images are not selfies because they are not products of the networked camera, they were not made with a camera of one’s smartphone and were not shared on social media networks. As simple as that.

The Impossibility of Capturing Butoh in Photography

“Neiespējamais butō tulkojums fotogrāfijā [The Impossibility of Capturing Butoh in Photography],” in Simona Orinska, ed., Butoh (Riga: Mansards, 2015), 68-79. In Latvian only. ISBN 9789934121098. Available from the publisher's website.

I’m grateful to Simona Orinska, the editor of this book and a butoh artist, for inviting me to contribute to this volume and to think about such a challenging topic.

Since 2011, when Orinska conceived the idea of the book and solicited the first drafts of the articles, I’ve had many chances to return to the topic and ask myself, how can I describe the relationships between butoh, a performance based on movement and emotion, and photography, a medium that freezes movement and removes all emotions?

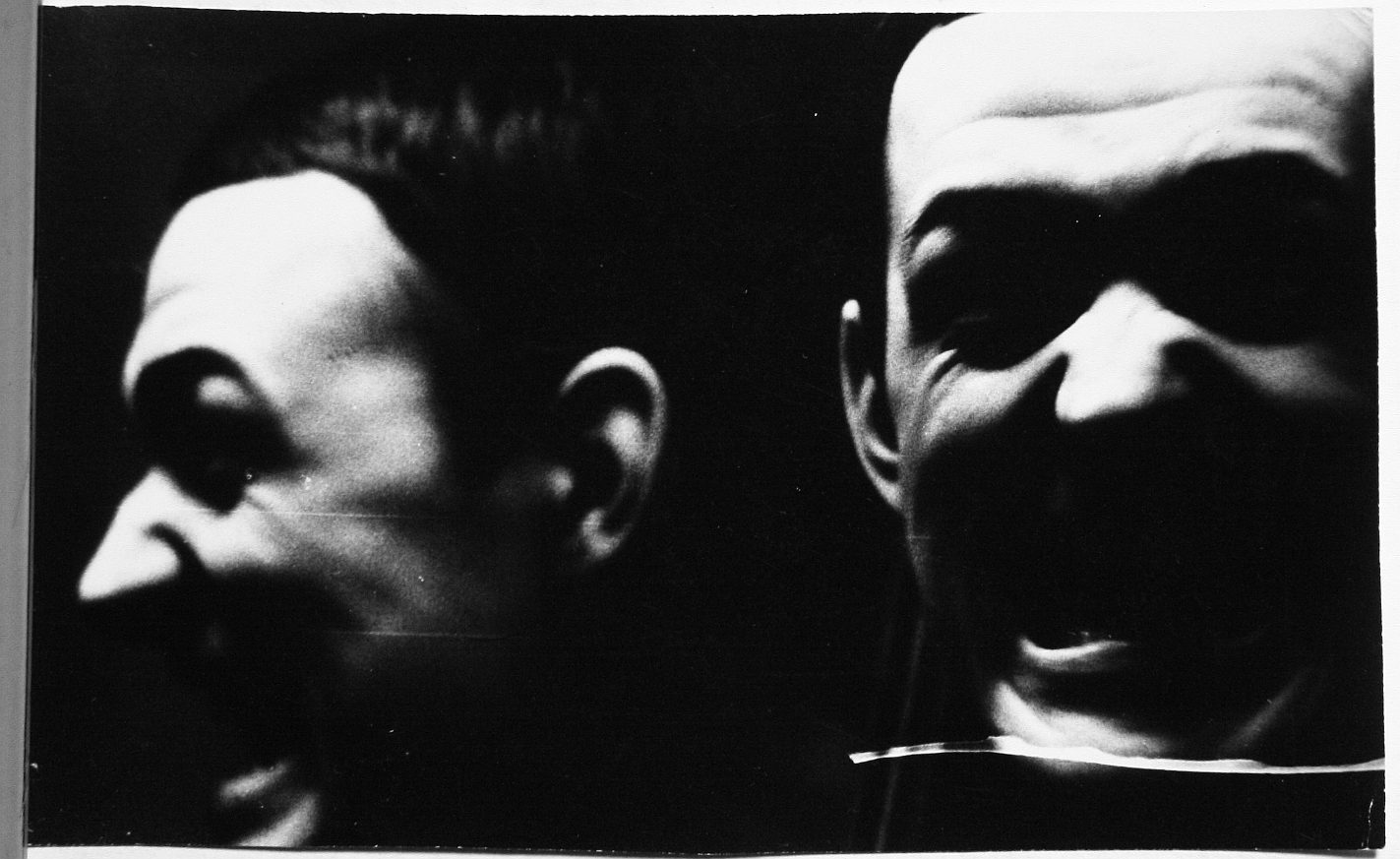

To address this question, in this article I revisit theoretical writings about the depiction of movement and dance in photography. I introduce a comparative reading of Kamaitachi (1968), a well-known series of photographs by Japanese photographer, Eikoh Hosoe (b. 1933), and Riga Pantomime (1964-1965), an almost unknown series by Latvian photographer and artist, Zenta Dzividzinska (1944-2011).

This comparison brings to the fore a similarly heightened expressiveness of human body and face that photographers captured in two different cultures: in butoh of the postwar Japan and pantomime in Latvia under the oppressive Soviet regime. Can there be two more different cultures as these? But a totally unexpected meeting point of these cultures appears in a photograph by Zenta Dzividzinska, Hiroshima (1964-1965), taken at a rehearsal of eponymous performance by pantomime troupe Riga Pantomime.

See below more photographs by Zenta Dzividzinska from the series Riga Pantomime (1964-1965). Most of the photographs from this series were never exhibited during the artist's lifetime, but a small selection of vintage prints recently was included in the exhibition Society Acts (September 20, 2014 - January 25, 2015) at the Moderna Museet, Malmö, Sweden. Read more about this exhibition and my short presentation of Dzividzinska's works at the Moderna Museet.

Steichen, The Artist and Propagandist

"The Artist and Propagandist: Steichen's Role at Two Decisive Moments in the History of American Photography," in Šelda Puķīte, ed., Edward Steichen. Photography (Riga: Latvian National Museum of Art, 2015), 33-37. ISBN 9789934512575. Published on the occasion of exhibition "Edward Steichen. Photography" at the Latvian National Museum of Art, The Arsenals Exhibition Hall, Riga, Latvia, June 26 – September 6, 2015.

Edward Steichen’s name is associated with the emergence of two aesthetically and thematically different and even oppositely oriented movements in photography. At the beginning of the 20th century Steichen was a pioneer of Pictorialism, and his 1904 photograph The Pond-Moonlight is a textbook example of this artistic style: intimate, romantic, timeless, and painterly.

Yet in the middle of the 20th century Steichen became a master of American political propaganda in photography and remains known for the creation of a radically new and different type of photography exhibition. In Steichen’s curated photography exhibitions, Road to Victory (1942) and The Family of Man (1955) at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, photographs lost their individuality, and the participating photographers’ original intentions were sacrificed for the sake of creating an atmosphere of patriotic pathos.

This article examines “Steichen the Pictorialist” and “Steichen the Curator,” the two contradictory directions in Steichen’s career and their interpretations by art historians in order to establish a broader context for the work on view in the current exhibition.

Selfiecity: Exploring Photography and Self-Fashioning in Social Media

“Selfiecity: Exploring Photography and Self-Fashioning in Social Media” (co-author Lev Manovich), in David M. Berry and Michael Dieter, eds., Postdigital Aesthetics: Art, Computation and Design (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), 109-122. ISBN 9781137437198.

NB: This is unedited working draft. Please refer to the book for the final published version of this chapter.

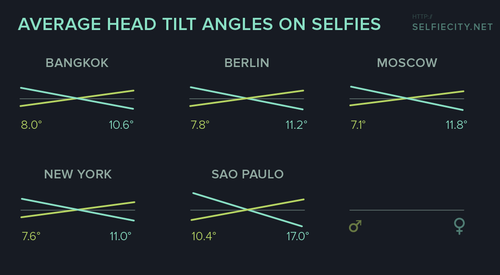

This chapter summarizes the methods and findings of the research project Selfiecity (2014).

User-generated visual media such as images and video shared on Instagram, YouTube, and Flickr open up fascinating opportunities for the study of digital visual culture and thinking about the postdigital. Since 2012, the research lab led by Lev Manovich (Software Studies Initiative, softwarestudies.com) has used computational and data visualization methods to analyze large numbers of Instagram photos. In our first project Phototrails, we analyzed and visualized 2.3 million Instagram photos shared by hundreds of thousands of people in 13 global cities.

Given that everybody is using the same Instagram app, with the same set of filters and image correction controls, and even the same image square size, and that users can learn from each other what kinds of subjects get most attention, how much variance between the cities do we find? Are networked apps such as Instagram creating a new universal visual language which erases local specifities? Does the ease of capturing, editing and sharing photos lead to more aesthetic diversity? Or does it, instead, lead to more repetition, uniformity and visual social mimicry, as food, cats, selfies, and other popular subjects drown everything else out?

In our project we wanted to show that no single interpetation of the selfie phenomenon is correct by itself. Instead, we wanted to reveal some of the inherent complexities of understanding the selfie – both as a product of the advancement of digital image making and online image sharing and a social phenomenon that can serve many functions (individual self-expression, communication, etc.).

By analyzing a large sample of selfies taken in specified geographical locations during the same time period, we argue that we can see beyond the individual agendas and outliers (such as the notorious celebrity selfies) and instead notice larger patterns, which sometimes contradict popular assumptions.

For example, considering all the media attention selfie has received since late 2013, it can easily be assumed that selfies must make up a significant part of images shared on Instagram. Paradoxically enough, our research revealed that only approximately four percent of all photographs posted on Instagram during one week were single person selfies.

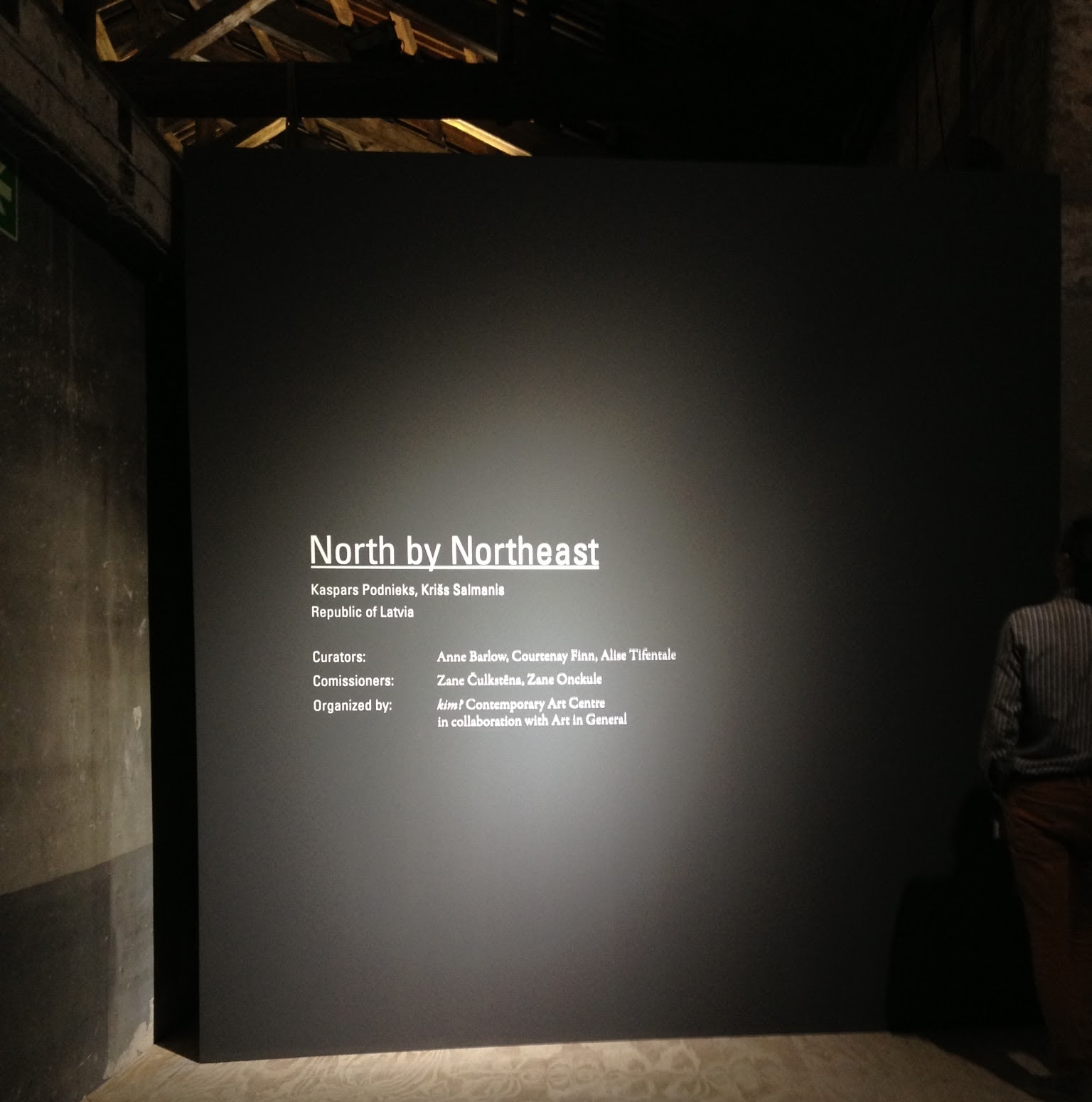

My introduction to the pavilion of Latvia at the 55th Venice Biennale

“Just What it is That Makes Latvian Art So Different, So Latvian?” in North by Northeast, Catalogue of the Pavilion of Latvia at the 55th International Art Exhibition La Biennale di Venezia (Riga: kim? Contemporary Art Center, 2013), 18-28. ISBN 9789934820076.

Cover of the catalogue. Photo: Ansis Starks. Courtesy Kim? Contemporary Art Center.

This is my introduction to North by Northeast, the Latvian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, co-curated by Anne Barlow, Courtenay Finn, and me.

North by Northeast in this Venice Biennale presents new works by two Latvian artists, Kaspars Podnieks and Krišs Salmanis. Both works can be misleading in their seemingly one-liner appearance. An upside-down tree and a series of black-and-white photographic portraits of farmers – is this a simple case of what you see is what you get? I would like to argue that it is rather the opposite – you are supposed to get what you actually do not see.

Latvian contemporary art is essentially a misunderstanding, an exception, or possibly a miracle. There is no tangible economic basis for the luxurious superstructure in this economically troubled country without a tradition of private funding for the arts. The audience for contemporary art is very limited, consisting of a tiny, economically, socially, and politically rather disenfranchised community of artists, art critics, and their families and friends. Besides, the long history of Soviet rule in Latvia developed a strong antipathy towards politically or socially explicit art. With a backdrop of highly politicized mass communication and visual culture, and ideologically charged official art, anything apolitical was seen as an escape, as a source of pleasure, sometimes even as a form of resistance. Speaking and reading between the lines was the major rhetorical strategy adapted by almost all social strata, equally employed in casual everyday conversations as well as in visual art, poetry, literature, and theater. The legacy of these generations is still very much present, therefore one should not expect a Latvian contemporary artist to be openly Marxist, anarchist, or any other sort of social revolutionary. What then should one expect? This essay attempts to articulate some possible answers.

From left: Kriss Salmanis, Alise Tifentale, and Kaspars Podnieks. 2013.

From left: Anne Barlow, Alise Tifentale, and Courtenay Finn. 2013.

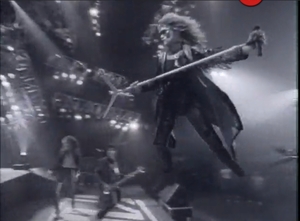

Western Rock Videos of the 1980s and 1990s in the Soviet Union

“'The Place I Wanted to Live In’: Western Rock Videos of the 1980s and 1990s in the Soviet Union,” in Maija Rudovska, ed., Inside and Out (Riga: kim? Contemporary Art Center, 2012), 2-9. ISBN 9789934820069.

Rock music is only possible when you are young. Rock stars on stage would jump and sweat through some kind of Dyonisian rituals, accompanied by the energetic, emotionally uplifting sound of their music. Live concert recordings made up a large part of the 1980s music videos, and the ecstatic atmosphere in these videos was often underlined by shots of excited fan crowds. For example, such videos as “You Give Love a Bad Name” (1986) by Bon Jovi, “Final Countdown” (1986) by Europe, “Love Removal Machine”, “Lil’Devil” (1987) and “Wild Hearted Son” (1991) by The Cult, “Everybody Loves Eileen” and “I’ll Never Let You Go” (1990) by Steelheart, and “Monkey Business” (1991) by Skid Row manifest this tendency.

The fact that these rock stars – men - are using make-up and have long, “feminine” hairdos, can suggest a certain sexual ambiguity or at least uncertainty. Or perhaps the tights, eyeliners, and perm rather functioned as attributes of emphasized masculinity? Manifestations of androgyny or uncertain gender identity in the "cock rock" world can be interpreted as a proletarian offspring of the aristocratic dandyism of the 18th and 19th centuries. For example, notice how the aesthetic refinement of George Byron, Oscar Wilde, and Aubrey Beardsley was recaptured by David Bowie in the 1970s. In the 1980s this sexual undecidability was reduced to the standard combo of long hair and skinny leather pants. If rock music of this era had any true macho hero at all, it could only have been the demonic Glenn Danzig, who at the time had the most athletic torso, the most menacing look, and who could easily tame an alligator with his bare hands (see the video for “I’m the One,” 1990).

The Origin of Homo Novus in Latvian Photography

“The Origin of Homo Novus in Latvian Photography,” in Helena Demakova, ed., Vilnis Vītoliņš. This is Latvia. Photographs 2007–2011 (Riga: Andrejsala. Riga Contemporary Art Museum & Satori, 2011), 14-27. ISBN 9789934804762.

The aim of this essay is to outline the historical background for the unusual photographic work of Vilnis Vītoliņš (b. 1955, Latvian) in the 2000s. In order to understand why his work is so outstanding and sometimes difficult to accept for the Latvian audiences, in this essay I offer a tour through the development of photographic aesthetics in Latvia during the second half of the 20th century. This "little history" of Latvian photography for this purpose starts in 1955, the year when Vītoliņš was born in Cesvaine, a small town in Latvia. Approximately at the same time, Edward Steichen opened the influential exhibition The Family of Man in the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Vilnis Vītoliņš. The Bridge of Islands (then Moscow Bridge). Riga, 1984. Gelatin silver print. 18x18 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Photographer Inta Ruka

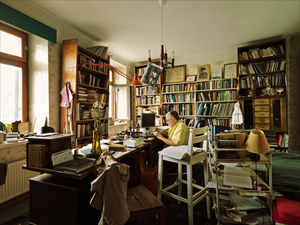

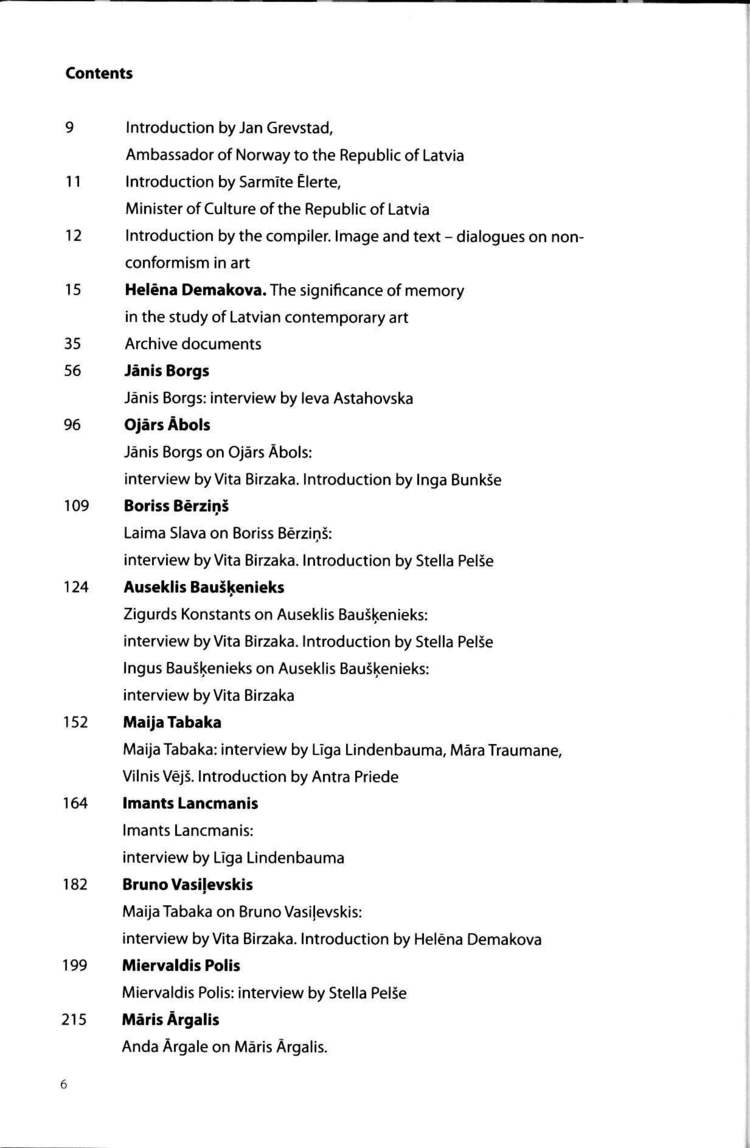

“Photographer Inta Ruka. [An interview with photographer Andrejs Grants],” in Helēna Demakova, ed., The Self. Personal Journeys to Contemporary Art: The 1960s–1980s in Soviet Latvia (Riga: Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Latvia, 2011), 364-374. ISBN 9789934801037.

Inta Ruka (b. 1958) is one of the most well-known Latvian photographers who has achieved great success in portraiture. Among her signature series are: My Country People (1983-1998), People I Have Met (1999-2004), and 5a Amalijas Street (2004-2008). The creative development of Ruka in the 1980s is closely related to the young generation that was defining its position in the photography of this decade, “the new wave of photography.” They turned to documentary material. The documentary as “un-manipulated” or “uncompromising” realism for them opened up new avenues for photography that were opposite to the principles of image making and aesthetics cultivated in the Latvian photographic art in the 1960s and 1970s.

Ruka and other then young photographers, including Andrejs Grants, attracted attention of the curators of art exhibitions at the end of the 1980s and beginning of the 1990s, such as Helena Demakova, Vid lngelevics, Philip Legros, Barbara Straka and others. Reviewing the catalogues of the first important exhibitions of Latvian photography in the West in the late l980s and early 1990s, one will always find the name of Ruka in the list of participants, along Andrejs Grants, Egons Spuris, Gvido Kajons, or Valts Kleins.

Grants and Ruka emerged from a milieu connected to The Ogre Camera Club, named after its location - a town not far from Riga. The club was led by photographer Egons Spuris, Ruka’s teacher and husband. Andrejs Grants in this conversation discusses the context and conditions under which the new wave of photography could arise in Latvia and such artists as Ruka develop.

From Photographic Art to Photography in Art

“From Photographic Art to Photography in Art,” in Ieva Astahovska, ed., Nineties. Contemporary Art in Latvia (Riga: The Latvian Center for Contemporary Art, 2010), 296-306.

Read moreIf We Really Do Love Art, We Live in It. The Image of Contemporary Art and Artist in Latvian Art Criticism of the 1990s

“If We Really Do Love Art, We Live in It. The Image of Contemporary Art and Artist in Latvian Art Criticism of the 1990s,” in Ieva Astahovska, ed., Nineties. Contemporary Art in Latvia (Riga: The Latvian Center for Contemporary Art, 2010), 108-119.

Read more