"Results of the Revision." Review of the exhibition And Others – Movements, Explorations and Artists in Latvia 1960–1984, Riga Art Space, Riga, Latvia, November 17 — December 30, 2010. Published in Studija 76, no. 1 (2011): 30-37.

Read moreBook review: Creative Networks by Rasa Smite

“When a Process Acquires Form and Becomes a Canon.” Review of Rasa Šmite, Creative Networks (Riga: RIXC Publishing, 2011). Published in Studija 81, no. 6 (2011).

Read moreExhibition review: Ostalgia at the New Museum, New York (Studija)

"We from Nowhere and Our Art." Review of exhibition Ostalgia at the New Museum, New York, July 6 - October 2, 2011. Published in Studija 81, no. 6 (2011).

Read moreThe Origin of Homo Novus in Latvian Photography

“The Origin of Homo Novus in Latvian Photography,” in Helena Demakova, ed., Vilnis Vītoliņš. This is Latvia. Photographs 2007–2011 (Riga: Andrejsala. Riga Contemporary Art Museum & Satori, 2011), 14-27. ISBN 9789934804762.

The aim of this essay is to outline the historical background for the unusual photographic work of Vilnis Vītoliņš (b. 1955, Latvian) in the 2000s. In order to understand why his work is so outstanding and sometimes difficult to accept for the Latvian audiences, in this essay I offer a tour through the development of photographic aesthetics in Latvia during the second half of the 20th century. This "little history" of Latvian photography for this purpose starts in 1955, the year when Vītoliņš was born in Cesvaine, a small town in Latvia. Approximately at the same time, Edward Steichen opened the influential exhibition The Family of Man in the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Vilnis Vītoliņš. The Bridge of Islands (then Moscow Bridge). Riga, 1984. Gelatin silver print. 18x18 cm. Courtesy the artist.

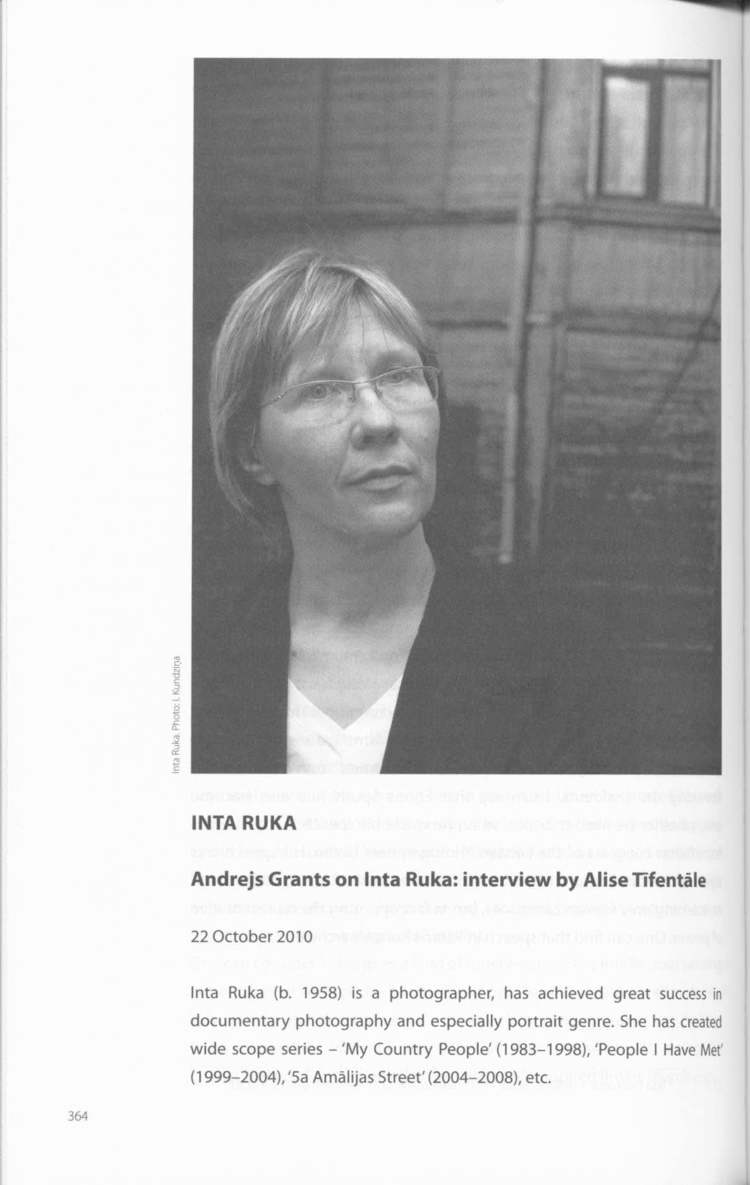

Photographer Inta Ruka

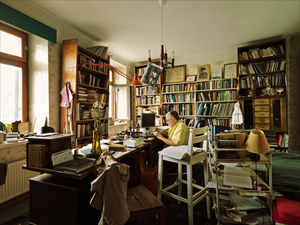

“Photographer Inta Ruka. [An interview with photographer Andrejs Grants],” in Helēna Demakova, ed., The Self. Personal Journeys to Contemporary Art: The 1960s–1980s in Soviet Latvia (Riga: Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Latvia, 2011), 364-374. ISBN 9789934801037.

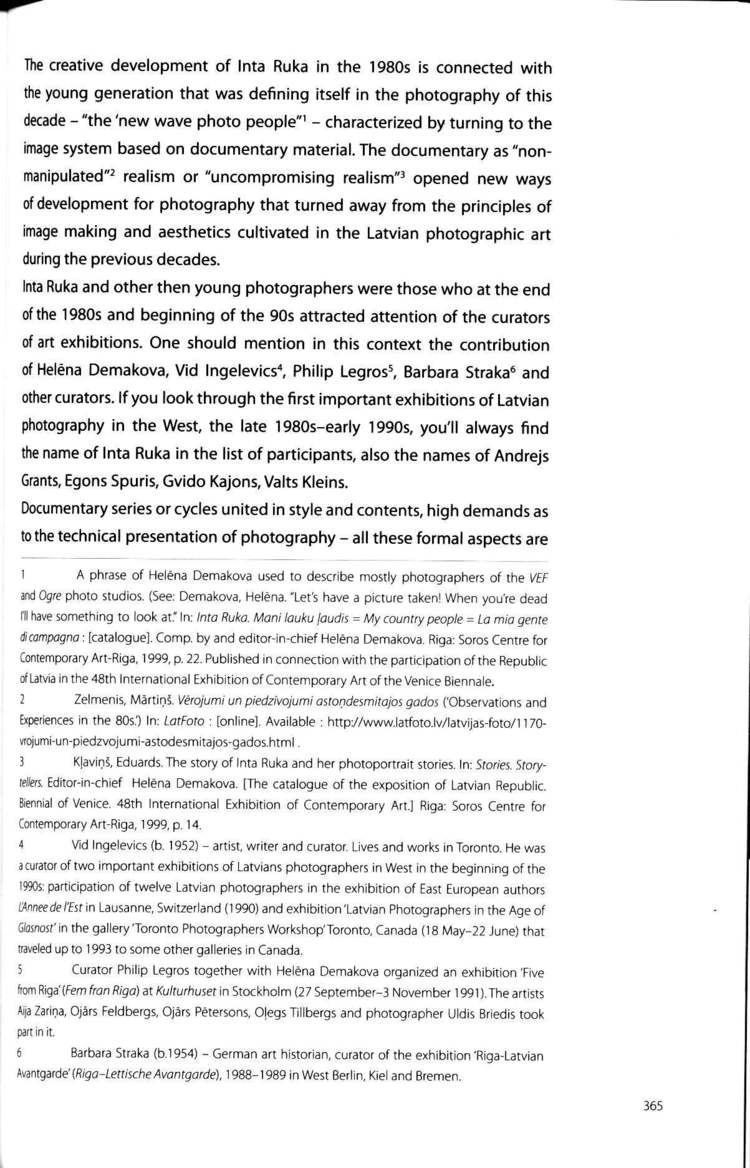

Inta Ruka (b. 1958) is one of the most well-known Latvian photographers who has achieved great success in portraiture. Among her signature series are: My Country People (1983-1998), People I Have Met (1999-2004), and 5a Amalijas Street (2004-2008). The creative development of Ruka in the 1980s is closely related to the young generation that was defining its position in the photography of this decade, “the new wave of photography.” They turned to documentary material. The documentary as “un-manipulated” or “uncompromising” realism for them opened up new avenues for photography that were opposite to the principles of image making and aesthetics cultivated in the Latvian photographic art in the 1960s and 1970s.

Ruka and other then young photographers, including Andrejs Grants, attracted attention of the curators of art exhibitions at the end of the 1980s and beginning of the 1990s, such as Helena Demakova, Vid lngelevics, Philip Legros, Barbara Straka and others. Reviewing the catalogues of the first important exhibitions of Latvian photography in the West in the late l980s and early 1990s, one will always find the name of Ruka in the list of participants, along Andrejs Grants, Egons Spuris, Gvido Kajons, or Valts Kleins.

Grants and Ruka emerged from a milieu connected to The Ogre Camera Club, named after its location - a town not far from Riga. The club was led by photographer Egons Spuris, Ruka’s teacher and husband. Andrejs Grants in this conversation discusses the context and conditions under which the new wave of photography could arise in Latvia and such artists as Ruka develop.

Five Sentences about Soviet Art

“Five Sentences about Soviet Art,” Dizaina Studija 29, no.2 (2011): 68-70.

Because Latvian art from the Soviet era is at the center of my academic research, I regularly encounter questions which are yet to be explained and solved. To what extent do the artworks from this era display a “Soviet” influence, how much is there of “Latvian” art, and how much is there simply “art”? Should the fact that photography at this time was included in the field of “amateur art” be the defining factor to continue interpreting it as "amateur" from today's perspective? Is it necessary to have a broader insight into the institutional structure of Soviet art and into (no doubt ideological) texts about Soviet art published in the press of that time? Or, alternatively, is it better to have a distanced outsider’s view concentrating only on the artworks themselves, rather than the circumstances of their making? Should we call the era in question the “Soviet period”, or perhaps it is enough to simply mention the decade in which the work was made? But isn’t it also important to remember that it was made under Soviet rule, which resulted in self-censorship and the inhibition of information exchange, personal movement and other restrictions?

Photographers Breaking the Iron Curtain: The Role of Informal International Communication Networks in Soviet Photography

“Photographers Breaking the Iron Curtain: The Role of Informal International Communication Networks in Soviet Photography.” Paper presented at the IAMCR (International Association for Media and Communication Research) annual conference Cities, Creativity, Connectivity, Kadir Has University, Istanbul, Turkey, July 13–17, 2011.

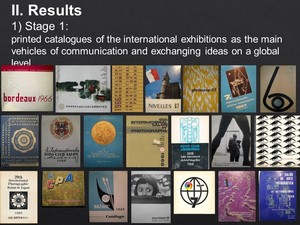

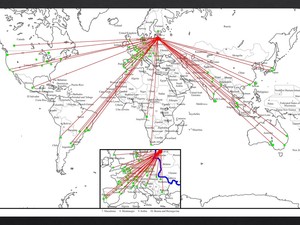

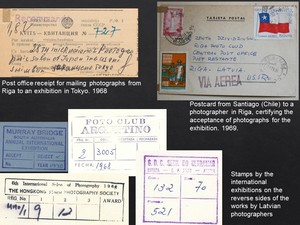

The paper discusses the role of the information exchange networks in the development of photography in the Soviet Union in the 1960s and 1970s, and presents a study on photographers from the Camera Club of Riga (Latvia) who managed metaphorically to break through the Iron Curtain and participated in photography exhibitions worldwide.

Although photography from the Soviet Union in general has been analyzed in different contexts both in post-Soviet countries and in the West, the specific fields of amateur photography and art photography in the 1960s and 1970s still have not been covered completely. Besides, history of photography in the Soviet Union often has been identified with history of Russian photography, only occasionally mentioning national schools of other Soviet republics with different cultural and social circumstances.

This paper outlines some of the complex issues related to the understanding of institutional framework of amateur and art photography in the Soviet Union in the 1960s and 1970s, and focuses in particular on Riga Camera Club (Latvia), an amateur organization that became one of the most visible hubs of creative photography in the Soviet Union in the 1960s, and whose members succeeded in participating in numerous international photography exhibitions outside the USSR.

The New Wave of Photography: The Role of Documentary Photography in Latvian Art Scene During the Glasnost Era

“The New Wave of Photography: The Role of Documentary Photography in Latvian Art Scene During the Glasnost Era” in Stephen Andrew Arbury and Aikaterini Georgoulia, eds., Visual and Performing Arts (Athens: Athens Institute for Education and Research, 2011), 121-128. Proceedings of the 2nd Annual International Conference on Visual and Performance Arts at the Athens Institute for Education and Research, Athens, Greece (6–9 June, 2011). ISBN 978960954965.

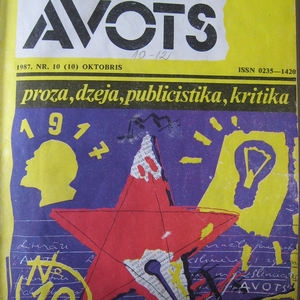

A major shift in the role and perception of photography as a medium of the visual arts in Latvia took place on the background of the political events in the mid-1980s that ultimately led to the collapse of Soviet Union and the Communist bloc. In Latvia, then one of the Soviet Republics, the idea of restoring the country’s independence dominated the public debates. Also the visual arts often were discussed in terms of the current political and social changes. Following the pattern of neglecting the past, in the mid-1980s a ‘new wave of photography’(Demakova, 1999) was rising in Latvia. The proposed paper describes the social and aesthetic context of the ‘new wave’ of Latvian photography, and discusses the role of the documentary imagery in the visual arts. Although Latvian photographers were ‘freed to picture even the ugliest truths’ (Svede 2004), the new documentary imagery was not confused with photojournalism with its more direct and sometimes aggressive stances and rarely it represented any ‘shock-pleasure’ (Welchman, 1994)value associated in the West with photography from the Soviet Union.

The paper analyses the photographs that ‘shifted into the dominant “fine art” context’ within the specific Soviet and early post-Soviet visual culture in Latvia. Several Latvian photographers earned recognition during the late 1980s after their participation in exhibitions outside the Soviet Union. These photographers shaped and defined photography as one of the ‘new media’ (Demakova, 2000) in Latvian contemporary art of the early 1990s.The paper adds an insight into the changing attitudes towards documentary photography in Latvia during the glasnost era.